Bluestocking in Patagonia Reviews

Bluestocking in Patagonia Reviews

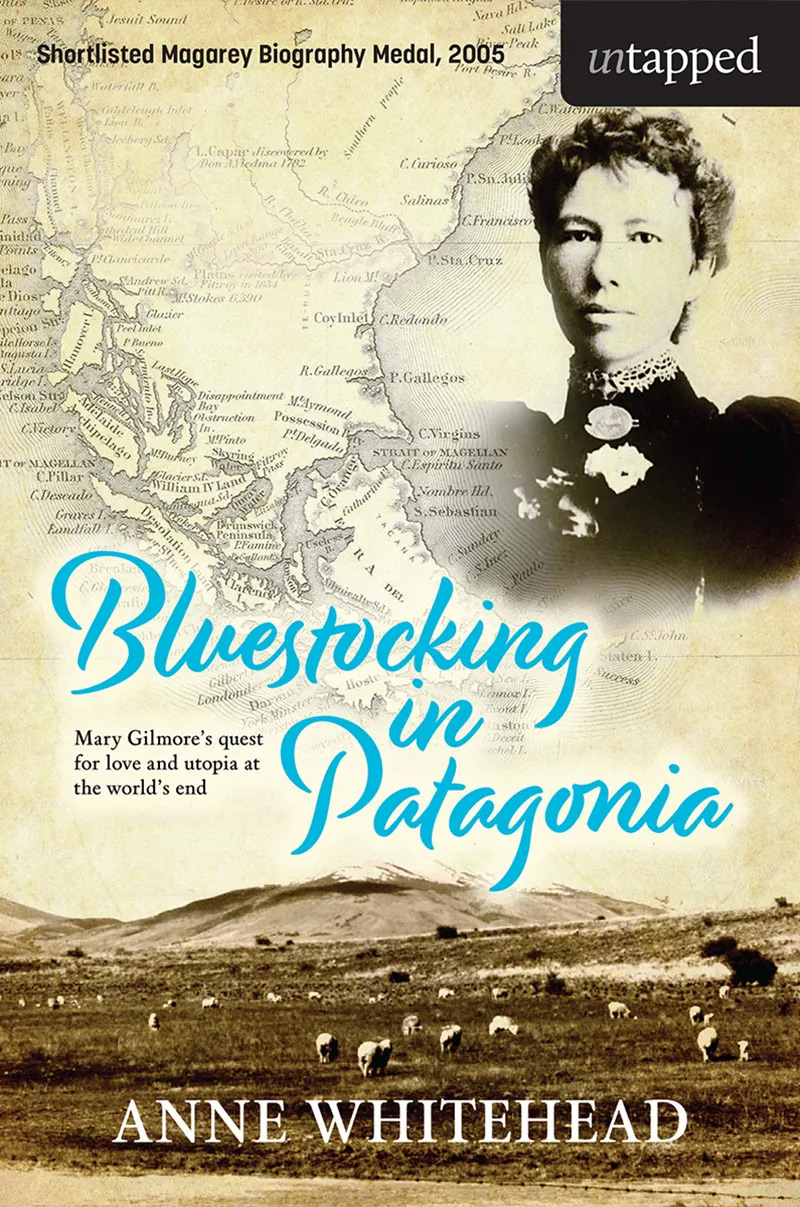

Judges' Citation shortlisting Bluestocking for 2005 Australian Magarey Medal for Biography

‘Anne Whitehead gives her story a compelling immediacy by weaving the historical account of [Mary] Gilmore’s life ‘at the world’s end’ with her own present-day travels in Gilmore’s footsteps, traversing the great Parana River from Buenos Aires to Asuncion, experiencing the isolation and climatic extremes of Colonia Cosme, where the Australian experiment faltered, visiting the desolate estancia in Patagonia where Will Gilmore worked as a shearer and Mary, briefly, as governess. Combined with effective use of contemporary and current newspaper and travellers’ accounts and interviews with descendants of colonists and employers, this strategy gives depth and richness to this account of six extraordinary and relatively unknown years in the life of one of Australia’s iconic figures.’

Shortlisted for 2005 Australian Magarey Medal for Biography

Extracts from reviews:

'I shall take away Bluestocking in Patagonia, by Anne Whitehead (Profile), the story of Mary Gilmore, poet, pioneer, utopian and sheep-shearer's wife, whose face is on the Australian $10 note. I need to know how it got there.'

Hilary Mantel

Summer reading - Arts Telegraph, UK 19 July 2003

'... Anne Whitehead intersperses this biography with the details of her own research, which included travelling in Mary Gilmore's footsteps. After an initial reservation that the author would intrude on her subject's turf, I quickly fell under the spell of Whitehead's intelligent writing. Her capacity for research is combined with a breadth of knowledge that enables her to explore creatively the life of her subject and the people with whom she was living. It is a biography that compassionately embraces the artistic, emotional and political aspects of Mary Gilmore's life. In particular, it is a homage to South America.'

Dianne Dempsey

The Age, 19 July 2003

'This is the tale of the early adult life of the poet, radical socialist and campaigner Mary Gilmore… And a great tale it is too. Mary Cameron (later Gilmore), a restless intellectual determined to follow her socialist star, emigrates to Paraguay to co-found a utopian commune. Of course, it all rapidly falls apart… At that point you could say the ideal has started to become an ordeal, and this is where her struggle to cope with the harsh reality of socialist idealism is at its most dramatic.

If Bluestocking in Patagonia merely covered Gilmore's time in Paraguay, this book would be good enough, because it's a beautifully written, well-told story. But there's more to it. Anne Whitehead takes the serious risk of mixing her historical academic research with her own experiences in tracking down this part of Gilmore's life. Tales of authors following in their hero's footsteps can easily descend into self-indulgent swill, but Whitehead avoids this and the result is surprisingly entertaining. There should be more books like this.'

If Bluestocking in Patagonia merely covered Gilmore's time in Paraguay, this book would be good enough, because it's a beautifully written, well-told story. But there's more to it. Anne Whitehead takes the serious risk of mixing her historical academic research with her own experiences in tracking down this part of Gilmore's life. Tales of authors following in their hero's footsteps can easily descend into self-indulgent swill, but Whitehead avoids this and the result is surprisingly entertaining. There should be more books like this.'

Nick Smith

Geographical (Journal of the Royal Geographical Society), UK, 1 Aug 2003

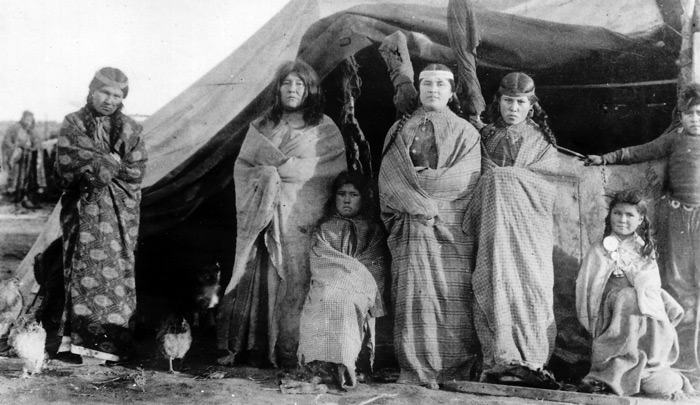

'Mary Gilmore (born Cameron) was made a Dame of the British Empire in 1937 for her contribution to Australian literature and social reform… but she also participated in one of the most bizarre episodes of Australian social history, when in 1895 she set sail for Paraguay. Nueva Australia was the bold name of the settlement which Gilmore's friend, the British socialist journalist and autocrat William Lane, founded on a plot of Paraguayan jungle in 1893… The utopian experiment was conceived as teetotal and racially pure, but within a few months the Nueva Australians had begun to consort and drink with the local women. Angry and disillusioned, Lane marshalled sixty-three of his most ardent supporters and established another, even more isolated utopian village, Colonia Cosme. It was here that Mary Cameron arrived on horseback and unpacked her trunk. She was thirty, single and was hoping to marry Lane's lieutenant, with whom she had struck up a friendship in Sydney. That he was barely civil towards her must have been more than dispiriting.

Anne Whitehead has chronicled the history of this and similar settlements in her earlier Paradise Mislaid: In Search of the Australian Tribe of Paraguay (1998), and says little about them here beyond cataloguing basic facts. In Bluestocking in Patagonia she focuses on the two years that Mary spent trying to leave South America and return home, after Lane had turned his back on the second colony. Not long after arriving in Paraguay, she married William Gilmore, a good-natured, illiterate sheep-shearer, with whom she had a son, Billy, and together all three managed to reach Argentina in search of work on its vast estancias. Whitehead's is a slender story, but by assiduously following in her subject's footsteps she fleshes it out with an informed and lively account of her own travels. Patagonia is a rich source of curious incidents and eccentric people, and Whitehead makes the most of these, describing the Welsh towns of Trelew and Puerto Madryn, where Taffs still sing contentedly and serve bara brith in tourist tea shops; a robbery pulled off by Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid; Charles Darwin's forays from the Beagle; W.H. Hudson's delight in the birds of the region, and the search for the giant sloth carried out by Mr Hesketh Prichard of the Daily Express . She mentions Bruce Chatwin, who turned up unannounced at the great estancia of Killik Aike, where the Gilmores had lived for some months, only to be sent away "with a flea in his ear" by its current owners. Mary Gilmore left Killik Aike abruptly too, after she had befriended a young peon, a transgression for any woman, made worse because Mary was white.

Gilmore weathered the unrest of war between Argentina and Chile, though her nerves and her health had begun to fail. Whitehead quotes extensively from her letters to William, who had remained at Killik Aike while she left with Billy to teach English in the frontier town of Rio Gallegos. These letters reflect a courageous, resourceful and strong-willed woman. The Gilmores eventually returned to Australia, and set up home in rural Victoria. William found work as an itinerant labourer, but Mary was miserable. In 1910 she moved to Sydney and, finally, was able to devote herself to her poetry, as well as to burn up her energies in social causes, becoming an important early critic of Australia's treatment of Aboriginals. "Yea! I have lived" was how she began one poem, and reading Anne Whitehead's spry account of her life, it is hard not to agree.'

Anne Whitehead has chronicled the history of this and similar settlements in her earlier Paradise Mislaid: In Search of the Australian Tribe of Paraguay (1998), and says little about them here beyond cataloguing basic facts. In Bluestocking in Patagonia she focuses on the two years that Mary spent trying to leave South America and return home, after Lane had turned his back on the second colony. Not long after arriving in Paraguay, she married William Gilmore, a good-natured, illiterate sheep-shearer, with whom she had a son, Billy, and together all three managed to reach Argentina in search of work on its vast estancias. Whitehead's is a slender story, but by assiduously following in her subject's footsteps she fleshes it out with an informed and lively account of her own travels. Patagonia is a rich source of curious incidents and eccentric people, and Whitehead makes the most of these, describing the Welsh towns of Trelew and Puerto Madryn, where Taffs still sing contentedly and serve bara brith in tourist tea shops; a robbery pulled off by Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid; Charles Darwin's forays from the Beagle; W.H. Hudson's delight in the birds of the region, and the search for the giant sloth carried out by Mr Hesketh Prichard of the Daily Express . She mentions Bruce Chatwin, who turned up unannounced at the great estancia of Killik Aike, where the Gilmores had lived for some months, only to be sent away "with a flea in his ear" by its current owners. Mary Gilmore left Killik Aike abruptly too, after she had befriended a young peon, a transgression for any woman, made worse because Mary was white.

Gilmore weathered the unrest of war between Argentina and Chile, though her nerves and her health had begun to fail. Whitehead quotes extensively from her letters to William, who had remained at Killik Aike while she left with Billy to teach English in the frontier town of Rio Gallegos. These letters reflect a courageous, resourceful and strong-willed woman. The Gilmores eventually returned to Australia, and set up home in rural Victoria. William found work as an itinerant labourer, but Mary was miserable. In 1910 she moved to Sydney and, finally, was able to devote herself to her poetry, as well as to burn up her energies in social causes, becoming an important early critic of Australia's treatment of Aboriginals. "Yea! I have lived" was how she began one poem, and reading Anne Whitehead's spry account of her life, it is hard not to agree.'

Nicola Walker

Times Literary Supplement, 14 Nov 2003

‘The core of Whitehead's narrative consists in following the steps of the Gilmore family from Paraguay southwards into Patagonia, but each step, either through location or event, allows a branching out into Argentina's past history and its present condition. At one level, Whitehead's book has the engagingly tangential quality of lively gossip (including family photographs), but its layering of material and the quality of research and observation make it something more complex and significant...

Bluestocking in Patagonia is eminently readable, its structural artifice just perceptible enough to be pleasing, its style commendably lucid. The extensive documentation supports a view of Whitehead as a careful and credible historian... It deserves a popular success. From beginning to end, in its readability, its engaging narrative and its shrewd evocation of personalities and places past and present, it meets the classical criterion of being both instructive and entertaining.'

Bluestocking in Patagonia is eminently readable, its structural artifice just perceptible enough to be pleasing, its style commendably lucid. The extensive documentation supports a view of Whitehead as a careful and credible historian... It deserves a popular success. From beginning to end, in its readability, its engaging narrative and its shrewd evocation of personalities and places past and present, it meets the classical criterion of being both instructive and entertaining.'

Dr Jennifer Strauss

Australian Book Review, August 2003

‘Bluestocking in Patagonia is a very beautiful book. In the first place, Whitehead writes with considerable flair, and with a fine eye for detail. The text is intelligently crafted, switching between Australia and South America, past and present, self and other… Whitehead is a thorough and accomplished researcher - in both the library and "the field" - yet one who knows that the mere display of erudition is liable to produce bad history. This book is also valuable because it explores, in considerable detail, an episode in the career of Mary Gilmore that has not been subjected to such close attention previously...

Yet Bluestocking in Patagonia is important for other reasons. This book is as much about Whitehead's effort to retrace Gilmore's steps as about Gilmore herself and is, in this respect, a fine blend of history and travel writing: a combination we also find in Whitehead's earlier book on the Paraguayan colonists... There were occasions, especially early in her book, on which I found myself resisting Whitehead's habit of digression. Yet her account of the sad condition of present-day Argentina, such a contrast with the high hopes of a century ago, parallels the failure of Lane's Utopian socialist dream. Just as Lane's, and Gilmore's Utopianism contained much that was mean - such as a nasty racial bigotry - Argentina's hopes were underpinned by the extermination of Indigenous people and brutal treatment of the poor. The last chapter of the book is devoted to an account of the 1921 massacre of hundreds of striking workers in Patagonia at the hands of the Argentine authorities and instigation of British capitalists…

There is a delicious irony here. The "New Australia" Utopian experiment is usually presented in the context of the radical nationalism of the 1890s and Gilmore herself would, in due course, become an icon of Australian nationalism. Yet Whitehead's account reveals both the reality, and the slipperiness of Australian identity in the context of the nineteenth-century British diaspora. In South America Mary Gilmore sought Utopia, but found herself in another corner of Greater Britain.'

Yet Bluestocking in Patagonia is important for other reasons. This book is as much about Whitehead's effort to retrace Gilmore's steps as about Gilmore herself and is, in this respect, a fine blend of history and travel writing: a combination we also find in Whitehead's earlier book on the Paraguayan colonists... There were occasions, especially early in her book, on which I found myself resisting Whitehead's habit of digression. Yet her account of the sad condition of present-day Argentina, such a contrast with the high hopes of a century ago, parallels the failure of Lane's Utopian socialist dream. Just as Lane's, and Gilmore's Utopianism contained much that was mean - such as a nasty racial bigotry - Argentina's hopes were underpinned by the extermination of Indigenous people and brutal treatment of the poor. The last chapter of the book is devoted to an account of the 1921 massacre of hundreds of striking workers in Patagonia at the hands of the Argentine authorities and instigation of British capitalists…

There is a delicious irony here. The "New Australia" Utopian experiment is usually presented in the context of the radical nationalism of the 1890s and Gilmore herself would, in due course, become an icon of Australian nationalism. Yet Whitehead's account reveals both the reality, and the slipperiness of Australian identity in the context of the nineteenth-century British diaspora. In South America Mary Gilmore sought Utopia, but found herself in another corner of Greater Britain.'

Professor Frank Bongiorno

Australian Literary Studies, Vol 22, No 3, 2006

'Anne Whitehead has followed Mary's footsteps, has listened to her voice in letters, diaries and poems and has found historical records and stories linked to her life in South America. She also knows much about the people Mary would have lived amongst and the sort of society she would have experienced at that time. This book is a fascinating synthesis of all this, and it is an unusual book. Bluestocking in Patagonia is as much a modern travel book as it is a biography of Mary Gilmore... Anne Whitehead is an excellent story-teller, a well-informed scholar and, like Mary, an intrepid traveller. I found her accounts of her own travels in South America equally as interesting as her glimpses of Mary's life. And I would recommend this book to anyone who enjoys good travel-writing, whether they have heard of Mary Gilmore before or not.'

Ann Skea

Mid-West Book Review Magazine, US, Oct 2003

'... Anne Whitehead's account of poet and civil rights activist Mary Cameron, the current incumbent on the Australian 10 dollar note and onetime resident of Colonia Cosme, makes fascinating reading... Whitehead's account, based largely on Cameron's letters and diaries, provides an intriguing insight into Cameron's loves, fears, adventures, homemaking, aspirations and philosophies. Some experiences are moving and inspirational. Recounting the long and distressing periods she spent apart from her husband, the hideous massacres of the Indians by General Roca and the corruption of the (mostly Scottish) estancia owners, Whitehead conveys the pain and despair of this dangerous land...'

Steve Wilcockson

Eastern Daily Press, UK, 9 Aug 2003

'Sydney-based Anne Whitehead's credentials as historical investigator are well laid. Paradise Mislaid , her lively account of the failed socialist colony in Paraguay in the 1890s, won the 1998 NSW Premier's Award in the category of Australian history. Her various trips to research that little-known tale obviously inspired her to explore the specific topic of Gilmore's South American sojourn. Whitehead plays the detective with relish, tracking evidence of modest cottages in miserably remote settlements where Mary lived after the Gilmores left the fragmented colony. She mostly stayed alone with their little son, braving winters in wool-lined clogs and lambskin petticoats while her husband was off shearing in the great estancias of Argentina and, later, Patagonia...

The author describes her own journeys and weaves in Mary's tales (verified and imagined)... the writing is consistently compelling, and, frequently, beautifully descriptive... The abundance of letters, however, provided the wealth of particular detail that Whitehead needed to complete her quest. Her research was assisted by "a cache of [Mary's] writings, most never published" that she discovered in Sydney's Mitchell Library. She also draws on the more contemporary observations of Bruce Chatwin and Paul Theroux in Patagonia and valuable sources such as Charles Darwin's Beagle journals, plus sniffy comments from today's estancia owners who agree the "radical" Australian bluestocking (who, shockingly, championed women's franchise and befriended servants) would never have fitted in.

Mary spent almost seven years in South America, returning home via London, where her old friend Lawson declared himself "simply mad for the sight of an Australian face". Her marriage didn't survive but her achievements as poet and social campaigner most certainly do. How different her life might have been had she and Lawson, who obviously loved her, made a life together - perhaps they would have ended up on either side of the $10 bill. It's a companionable equality that surely would have pleased her.'

The author describes her own journeys and weaves in Mary's tales (verified and imagined)... the writing is consistently compelling, and, frequently, beautifully descriptive... The abundance of letters, however, provided the wealth of particular detail that Whitehead needed to complete her quest. Her research was assisted by "a cache of [Mary's] writings, most never published" that she discovered in Sydney's Mitchell Library. She also draws on the more contemporary observations of Bruce Chatwin and Paul Theroux in Patagonia and valuable sources such as Charles Darwin's Beagle journals, plus sniffy comments from today's estancia owners who agree the "radical" Australian bluestocking (who, shockingly, championed women's franchise and befriended servants) would never have fitted in.

Mary spent almost seven years in South America, returning home via London, where her old friend Lawson declared himself "simply mad for the sight of an Australian face". Her marriage didn't survive but her achievements as poet and social campaigner most certainly do. How different her life might have been had she and Lawson, who obviously loved her, made a life together - perhaps they would have ended up on either side of the $10 bill. It's a companionable equality that surely would have pleased her.'

Susan Kurosawa

Weekend Australian, 19 July 2003

Poet, author and journalist Mary Gilmore graces our $10 note in honour of her passionate verse and campaigns for the rights of workers, children, women and Aborigines. Bluestocking in Patagonia traces the formative years that she spent in South America from 1895 to 1902… it’s fascinating to share a journey tinged with loss and disappointment, and to consider how these years transformed the woman we grew to love. Gilmore’s Dobell-painted likeness on our currency clearly deserves more caring consideration.’

Sarah MacDonald

SMH Spectrum, 26 July 2003

Profile Books UK, hb 2003, pb 2004 (ISBN 1 86197 504 X)